The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel (3rd English Edition, 1695)

The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel (3rd English Edition, 1695)

Author: Machiavel, Nicolas (Nicollo Machiavelli)

Title: The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel, Citizen and Secretary of Florence

Subtitle: Written Originally in Italian, And thence newly and faithfully Translated into English

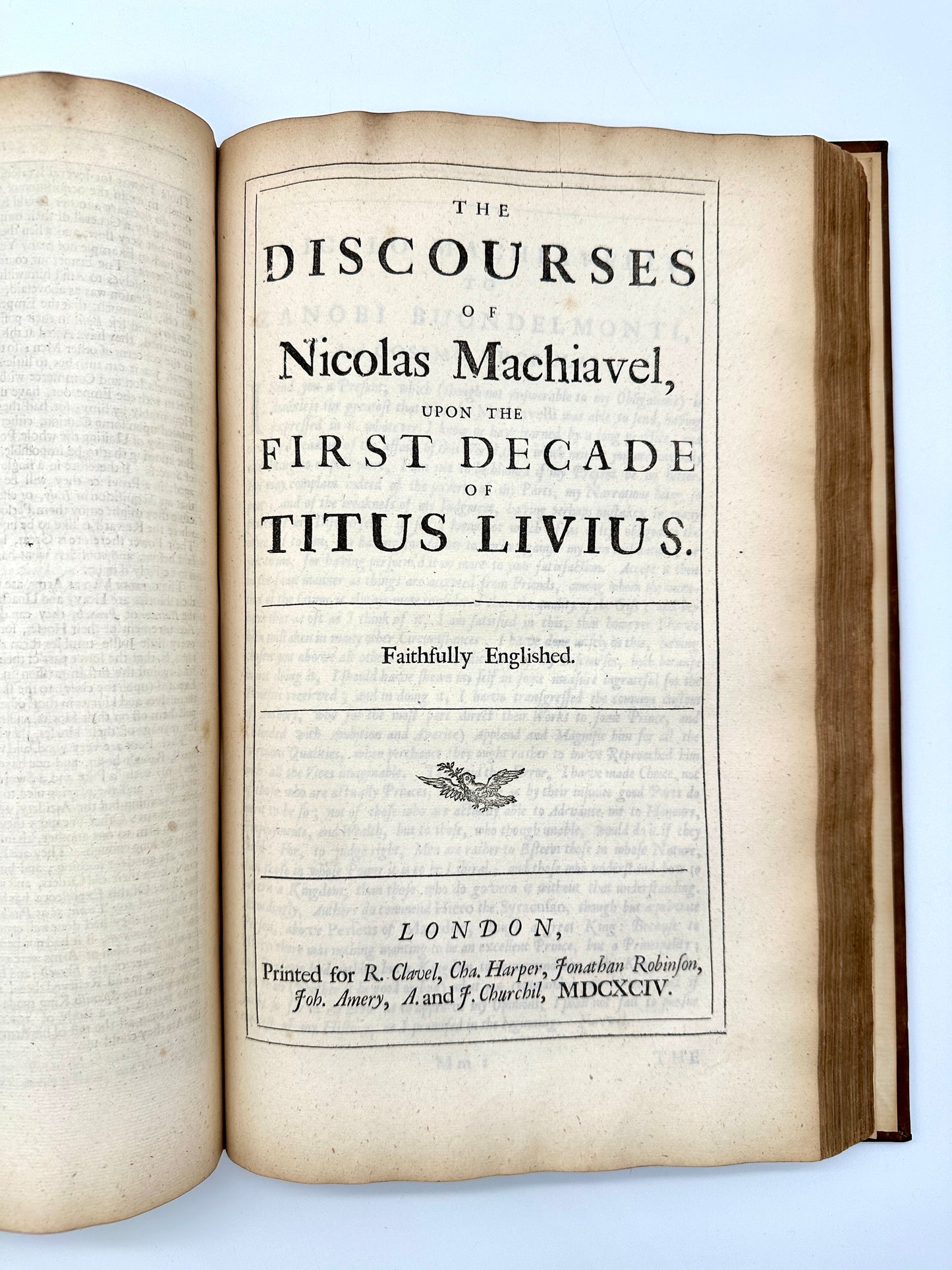

Publisher: R. Clavel, C. Harper, J. Amery, J Robinson, A. and J. Churchil

Date: 1695

Place: London

Dimensions: Folio. 32cm x 20cm

3rd edition, 2nd issue, with 1695 cancel title page.

131 in Wing’s Short Title Catalogue – Vol II (1641 - 1700)

Fine 19th century binding, polished calf with blind tooling to boards, 5 raised bands to spine. Gilt titles in maroon compartment, minor scuffing and edgewear to boards but very good indeed. Recent bookplate to front pastedown. New prelim and terminal blanks, new endpapers – a touch of browning to the edges of these.

Collated and complete – the erratic pagination is a feature of 17th century editions of this title. Pagination given in full below.

i(1695 Cancel title) + i(Misbound title page of The History of Florence) + vii + x(Table) + iv(Preface) + xii(Letter) +

The History of Florence in 8 Books

pp1-43, pp34, pp45-55, pp55, pp57-pp168, pp179-180, pp171-174, pp185-186, pp177, pp188-189 +

The Prince etc.

i(Title) + i(Author’s dedication) + pp199-pp262, pp265-267 +

The Discourses

i(Title) + i(Dedication) + pp267-pp314, pp317-430 +

i(Translation note) +

The Art of War in Seven Books + The Marriage of Belphegor

i(Title) + pp431 (misbound, final leaf of The Discourses) + pp433-528

Contains: The History of Florence, The Prince, The Original of the Guelf and Ghibilin Factions, Life of Castruccio Castracani, The Murther of Vitelli, &c. By Duke Valentino, The State of France, the State of Germany, The Discourses on Titus Livius, The Art of War, The Marriage of Belphegor, a Novel, Nicolas Machiavel’s Letter in Vindication of Himself and his Writings

Description

There is often contradicting information regarding 17th century editions of the Works. Wing lists 4 ‘editions’ up to 1700, however, the first English edition was published in 1674 and a second edition with the type reset, published in 1680. A third edition appeared in 1694. This is the second issue of the third edition, with a 1695 cancel title page.

In this edition, Nicolas Machiavel’s Letter in Vindication of Himself and his Writings includes a section on rebellion, suppressed in the first two editions.

In earlier copies it is bound in at the end, in this 1695 issue it is inserted at the front, after the indexes (Table) and the Publisher’s Preface to the Letter.

A very good copy indeed, with minor faults, most notable being the title page, which is a little soiled and browned. Minor (half line) pencil underlining to Letter. Minor pencil marginalia to pp4, a few minor chips to corners and fore-edges, not encroaching into the text, except slightly to a single leaf, where a 1.5cm part of the top rule – above the page number - is missing. A handful of closed tears to margins and small (<3mm) holes to a few leaves. Halfmoon tidemark to top margin, not encroaching into the text, at pp515 to pp518, corner margins chipped from pp523-228. Minor faults are noted, but this is an attractive, most desirable copy. The binding is tight and square, the leaves a little toned, but otherwise handsome and clean.

Historical Background

During the 17th century England fought a series of bloody civil wars that pitted Royalists - those who believed in the rule of an absolute monarch and the divine right of kings - against Parliamentarians, who demanded cession of political power to a more representative government. The Parliamentarians emerged victorious and in 1649 abolished both the House of Lords and the monarchy, executed the Stuart king Charles I and established The Commonwealth of England, over which Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector in 1653. For the first time since unification in the 10th Century, and for the last time since, England became, for a brief period, a Republic. This period is often referred to as the Interregnum and lasted 11 years. In 1660, shortly after Cromwell’s death and the resignation - due to lack of support from parliament and the military - of his named successor and son, Richard, England restored the Stuart monarchy: Charles II returned from exile in Europe to ascend the throne and rule alongside what had once again become a determinedly Royalist parliament.

Publication of the First Edition by the Opposition Bookseller John Starkey

It was during this period of Restoration that the London bookseller John Starkey published the first edition in English of the Works of Italian diplomat, historian and one of the most important political philosophers of the Early Modern period, Nicollo Machiavelli.

Starkey was “regarded by the government as a seditious newsmonger whose premises became associated with a radical club.” (Knights, 2006). Among these were followers of the natural-rights based political philosophy of John Locke, and those of political theorist James Harrington, a staunch Republican whose The Commonwealth of Oceana published during the Interregnum, set out a utopian vision for a representative political dispensation, immune to the unfairness inherent to monarchy. To this latter camp belonged former Rump MP Henry Neville, who some speculate might have had a hand in the publication of Harrington’s Oceana and to whom the translation of Machiavelli’s Works has traditionally been attributed. Harrington, Starkey and Neville were at different times all arrested and jailed on suspicion of treason after the Restoration.

As Knights notes: “Starkey was at the centre of an important network of those critical of Charles II's court and its policies, and...representative of the ideologically oriented bookseller whose role frequently overlapped with that of the 'author'.”

The Famous Letter

Starkey wrote a very sympathetic foreword to the Works, headed The Publisher to the Reader, Concerning the Following Letter. This letter is the apocryphal Nicholas Machiavel’s Letter to Zanobius Buondelmontius in Vindication of Himself and His Writings which was included in Starkey’s edition. According to Mahlberg, (2018) the letter has, since the 17th century, been recognised as a forgery, knowingly published by Starkey as a such, and most likely written by his friend and associate, Henry Neville*.

Probably as consequence of the letter’s attribution, Neville is also commonly given as the translator of the entire work; however Knights (2006) argues convincingly that the true translator was likely one John Bulteel**.

“Its (the letter’s) subject matter is the author’s defence against accusations of promoting democracy, atheism, and inciting rulers to villainous behaviour in his two major works, The Discourses and The Prince...In the process, Neville rehabilitates Machiavelli as a good Christian and repurposes him as a reformer of religion and the commonwealth.” (Mahlberg, 2018)

The Suppressed Section: Inciting Rebellion before and after the Glorious Revolution

As Mahlberg notes, however, the most interesting part of the letter is a section that was suppressed in the first two editions, though sometimes included in manuscript to “trusted readers” – i.e. trusted sympathisers, who were critical of the government, clergy and monarchy.

This part of the letter deals with rebellion. Neville’s fictitious Machiavelli does not consider rebellion to be ‘true rebellion’ if it is taken up “to maintain the Politick Constitution, or Government of his Country, in the condition it then is…to defend it from being changed.” Going to war with the ruling dispensation, then, was justified if “such taking up of Arms be Commanded or Authorised by those who are, by the Orders of that Government, legally instructed with the Custody of the Liberty of the People, and Foundation of the Government.”

Mahlberg points out how, in the English context this “unmistakeably implied that a rebellion against the monarch was legitimate if it served the defence of popular liberties and was authorised by Parliament.”

The printed inclusion of the suppressed section in the present edition is almost certainly due to its publication, 20 years later, in 1695, after The Glorious Revolution of 1688.

When Charles II died in 1685 he was succeeded by his brother, James II, who was disliked as a Catholic monarch for his decrees undermining the primacy of Protestantism. With the aide of influential religious and political leaders, William of Orange invaded England and ascended the throne with his queen Mary, sister of Charles II, thus establishing the supremacy of Parliament in political affairs and casting rebellion into new light.

The Present Edition and Remnant of Suppression

Examination of digital copies of the 1674 and 1680 editions shows that this is the first edition of the Works in which the Letter appears in full, i.e. with the suppressed section printed.

It was, however, separately published in full a few years earlier in 1691.

Tantalisingly, a palimpsest of its suppression remains - the catchwords at the foot of the 4th page - which should indicate the first words of the next – being printed from the same sheets as the previous edition - read “I am”. This corresponds with the start of the page following the suppressed page “I am charged, then in the second place, with impiety...” – the suppressed page, however starts: “Now having gone thus far in the Description of Rebellion...”.

The letter echoes Locke’s assertions in his Second Treatise about rebellion and revolution being not only justified, but in some instances morally demanded, when a tyrannical ruler or government undermines the liberties of their subjects. Notable is that, similar to Henry Neville publishing under the assumed name of Machiavelli, John Locke never published any political writings under his own name during his lifetime for fear of reprisal. It is clear, then, that in the context of 17th century England and indeed of early Modernism, the translation and publication of the Works was a politically and ideologically motivated, potentially seditious endeavour.

The Prince and the Discourses mark a distinctive and indeed radical break from the idealised, Utopian political theory of the ancient Greeks and present a realpolitik ostensibly required to successfully maintain power and rule effectively. The ‘Machiavellian’ approach to power has influenced politics, economics, international relations, popular culture and contemporary ideology since the 16th century. His influence is documented in the work and lives of political leaders as disparate as the American founding father John Adams, soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci. Even the rapper Tupac Shakur claimed to have read Machiavelli whilst incarcerated and is quoted as saying “I idolize that type of thinking where you do whatever's gonna make you achieve your goal."

* The Letter’s date is a give-away: 1 April 1537 – April Fool’s Day, some ten years after Machiavelli’s death.

** Although no translator is stated, either on the title page, nor elsewhere in the work, the Stationer’s Register for the year records the translator as ‘J.B.’ – Knights shows how, where Starkey provides this information elsewhere, it is generally reliable. Son of a French protestant minister, admirer of poetry, and, in his first work, proud of the independent citizenry of Cromwellian London, Bulteel seems a plausible candidate.

- Knight, Mark (2006) John Starkey and Ideological Networks in Late Seventeenth-Century England in Raymond, J. (ed) News Networks in Seventeenth-Century Britain and Europe. Routledge. London.

- Mahlberg, Gaby (2018) Machiavelli, Neville and the seventeenth-century English Republican attack on priestcraft, Intellectual History Review, 28:1, 79-99

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share