An Incunable Leaf (1483/4) from Margarita Poetica by Albrecht von Eyb

An Incunable Leaf (1483/4) from Margarita Poetica by Albrecht von Eyb

Author: von Eyb, Albrecht

Title: Single leaf from Margarita poetica

Printer: Printer of the Vitas patrum

Date: 1483/84

Place: Strasbourg

Dimensions: Folio. 26.5cm x 20cm

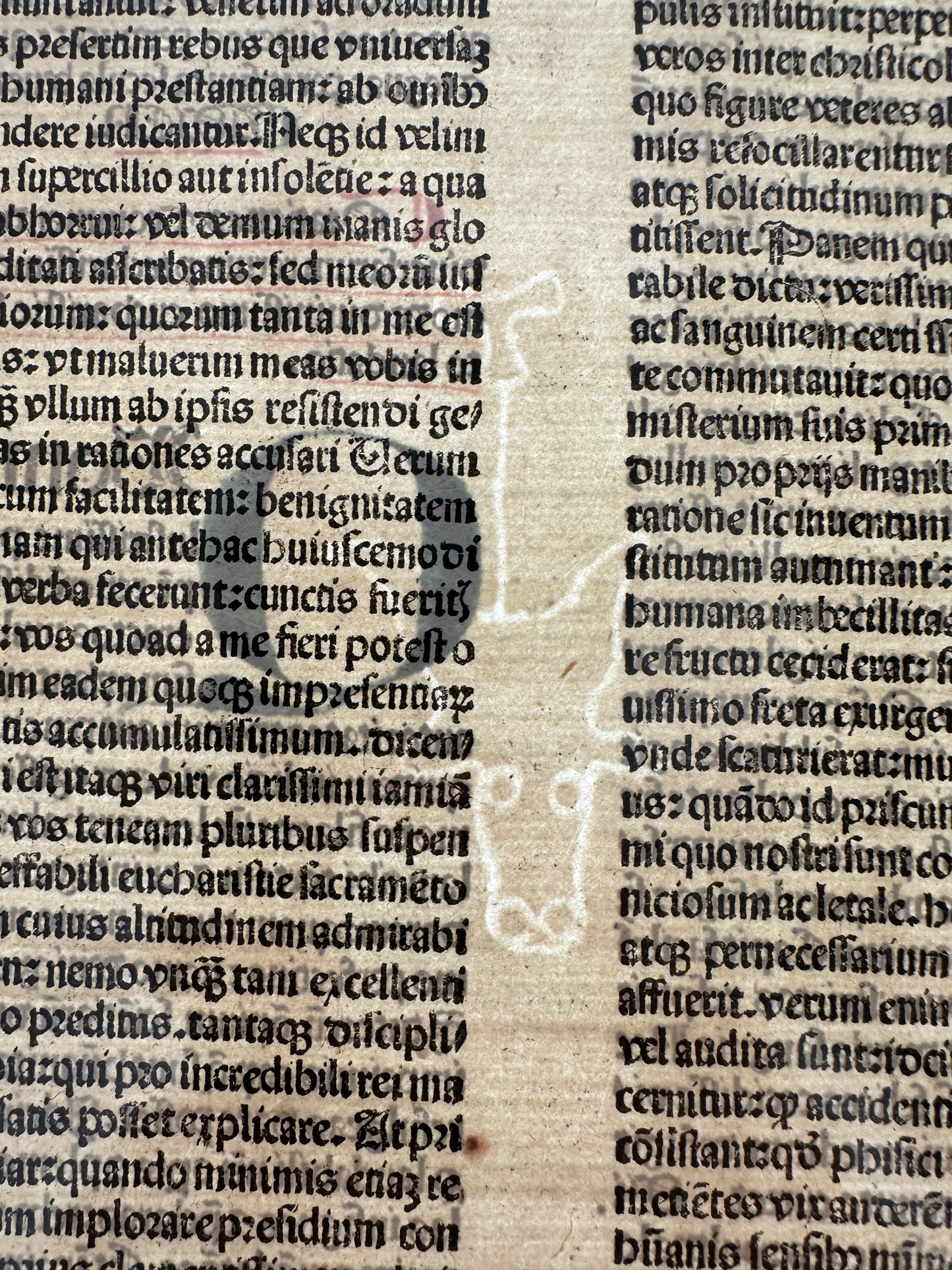

Incunable fragment of DW09533: a single leaf from Albrecht Eyb’s Margarita Poetica – or “literary pearl”, two columns, 44 lines of text in Gothic/Blackletter plus page headings. Contemporary shimmering mineral pigment illumination (in red and blue) and majiscule (capital letter) highlights in yellow to the recto. Near fine, with two small spots of foxing. Edges trimmed. The leaf contains a watermark of a bull’s head, with the letter T.

Incunable Fragment?

Incunabula (\ in-kyoo-nab-yuh-luh \ ) is a term coined by Hadrianus Junius in the 16th century, from the Latin incunabula meaning “cradle” or “swaddling clothes” referring to the infancy of book production using moveable type on a printing press. The printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in 1455 and marked a revolution in the dissemination of the written word, which previously was only produced in manuscript and therefore exceedingly rare, expensive and out of reach for the ordinary person. Printed items dating from the period 1455 to 1 January 1501 are called incunables or incunabula. Many of these printed items exist as ‘fragments’ i.e. parts of the volumes they initially belonged to.

Identifying an Incunable

One way of establishing the age of printed material is to identify watermarks in the paperstock. Presuming the leaf was an incunable, we consulted the database ‘Watermarks in Incunabula printed in the Low Countries (WILC)’ and successfully identified the watermark as WM I 55232 ('Bull’s Head, Letter Tau) dating the paper between 1477 and 1479. It was common for paper produced during this period to be used many years after production, but this confirmed that the paper was made during the incunable period. Next we used the Proctor/Haebler method for identifying early print type to try and narrow down the origin, i.e. the individual printing press that our leaf was printed on. Early printing presses each had a unique ‘fingerprint’ which can be determined by measuring in millimetres 20 lines of text and identifying the form of the capital ‘M’ (for Gothic typefaces) from 101 commonly used forms. We identified the type as 2:90G (the ‘90G’ representing 90mm for 20 lines of Gothic text) locating the press in Strasbourg, Germany where it was active between 1483 and 1487.

With the type and printer identified, we consulted the ‘Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke’ – a digital resource that allows a search of an ongoing project to catalogue known examples of incunable texts. Our search parameters included the number of lines of text, columns, print type and language of the text, narrowing down our search to 5 titles, examples of which are digitised by various institutions holding original copies. We identified the text from the headings ‘De Eucharistia / folio cclxiii’ (The Eucharist, page 263) and compared them to digitised incunables, eventually locating an identical leaf in the 1483/84 copy of Albrecht von Eyb’s Margarita poetica at The Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany.

About the Author and the Book

Albrecht von Eyb (1420-1475) was considered by at least one scholar (Hermann) to be the first true German humanist, in the sense of one who searches for “new principles of human conduct and interested in the reconstruction of the spiritual life in the light of human reason” (Hiller, J.A. 1939). As trade and cultural exchange between Italy and Germany expanded in the 14th century and as many German scholars attending Italian schools returned with progressive Italian ideas, a cosmopolitan humanism emerged as a broad, cultural, scientific and literary movement. Some of its aims were a revival of a venerated classical Roman antiquity and an opposition to the more benighted aspects of medieval society. Hiller, however, argues that despite von Eyb’s certain exposure to early humanism and humanistic ideas during his studies in Italy (in law and the Arts), the Margarita remains a text of “medieval moralism” both in form and content.

The first edition of Eyb’s Margarita was printed in Nurnberg in 1472 and it remained a popular book for at least a few years. “Printers of Germany, Italy, and France were responsible for fifteen editions from 1472 to 1503, of which one hundred and sixty-three copies are found today scattered over the libraries of Europe and America.” (ibid).

According to Hiller, “Eyb had a desire to bequeath to posterity the literary material which he had accumulated through the years of earnest toil and zeal in the vast cultural realm of his reading. For this purpose he collected an amazing array of quotations, orations, stories, poetry, and a variety of ‘other things’ (alia), as he writes, in order to present the best Latin phrases to the people of his beloved Germany...Fabricius observed that Eyb stressed two things throughout the Margarita: to be able to write well and to be disposed to live properly”

The Leaf

The leaf comprises the end of the second division of the Margarita which deals with standard phrases - mostly excerpts from other authors’ texts - in Latin, for the purpose of letter writing. The last excerpts, here represented on the first 2/3rds of the leaf, are from Seneca’s Tragedies and ends with the word ‘AMEN’ in capitals. Following this, on the final 1/3rd of the recto and the full text of the verso is the beginning of the 3rd division: Orations, “vibrant with the author’s personal and clerical views. The first of these orations is on the Eucharist. The author refers to the Hymn Lauda Sion, composed by St. Thomas; explains the true doctrine of the Eucharist and urges the more frequent reception of that sacrament.” (ibid)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share